Bearing Witness: Girls in the American Revolution

…But how, presumptuous shall we hope to find

Divine acceptance with the Almighty mind —

While yet (O deed ungenerous!) they disgrace

And hold in bondage Africa’s blameless race;

Let virtue reign — And those accord our prayers

Be victory ours, and generous freedom theirs.”

— Phillis Wheatley, writing in memory of Mary Wooster’s husband, July 15, 1778

How did girls experience the American Revolution? Much of our nation’s story is told through the adults who lived it, yet the Revolution — lasting for eight years — shaped the youth of an entire generation. It instilled a new set of values and ideals, which would firmly root concepts like Republican motherhood into the national consciousness. Yet it also brought about traumas, questions, and demands which would create a generation of women willing to question their society and women’s place in it.

Phillis Wheatley, Enslaved Poet

Phillis Wheatley is one of the very few Black voices recorded during this time. Enslaved in Senegal or Sierra Leone, then sold to the Wheatley family of Boston in 1761, Phillis was a domestic servant whose intellect was recognized and cultivated. A prolific poet, Phillis became the first Black woman to publish a book in America, with her popularity reaching its height just before the Revolution. Faced with mounting public pressure, the Wheatley family granted her freedom in 1774 — but kept her earnings, eventually leaving her destitute.

Phillis’s poems are evidence that Blacks did understand the Revolution’s goals — and how it left them out of the new nation. Of her 46 surviving poems, 18 express themes of freedom through a flight or voyage over water — imagery that was later used in slave spirituals as metaphors for death. She also wrote poems in memory of soldiers, like Mary Wooster’s husband, who died fighting for the new nation. Yet even in the elegy, Phillis took space to point out that Americans were fighting for independence while still holding in bondage “Africa’s blameless race.” As voice for millions of Blacks, Phillis saw both the hope — and hypocrisy — of the new nation.

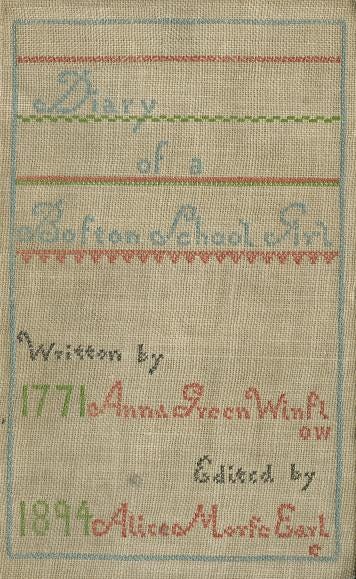

Anna Greene Winslow, Daughter of Liberty

Another Boston-based witness was Anna Greene Winslow, who recorded the prelude to war from November 18, 1771, to May 31, 1773 in her diary (which you can read online here). The daughter of a British officer, Anna was living with her aunt and attending school. While most of her diary focuses on everyday tasks and social occasions, it also contains mentions of the Daughters of Liberty, which arose in 1766 as a way for women to participate in the movement for independence. Despite her families allegiances, Anna expressed allegiance to the Daughters of Liberty, writing on February 21, 1772:

“As I am (as we say) a daughter of liberty I choose to wear as much of our manufactory as [possible].”

Anna wrote multiple entries about her pride in wearing clothing of her own manufacture. For girls like Anna, wearing homespun goods — that is, clothing made by their own hands, or by other Americans, rather than imported from Britain — was one way to support the Revolution. It dealt a substantial blow to British merchants, who depended on American buyers for profit; ultimately, these boycotts would reshape Atlantic trade networks and prove that women’s roles as household decision makers could have profound political and economic consequences. For Anna, her decisions were even more profound: as the daughter of a British officer, she was not only rebelling against her country — she was rebelling against her father’s authority, breaking the social norms of her time.

Anna Rawle, Loyalist

Not all Loyalist’s Daughters broke with their families. Anna Rawle of Philadelphia bore witness to the end of the Revolution, writing in her diary during the days immediately following General Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown (you can read the full excerpt here). Though you might think a surrender would bring peace, it did just the opposite: Loyalists across the country were attacked by mobs intent on driving them out of the country.

Anna Rawle spent her late teens witnessing the Revolution and was twenty-four years old when Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781. In the days following, she wrote that the rumors of Cornwallis’s surrender was “as surprising as vexatious” and could “neither read, work or give my attention one moment to anything” until they received letters that confirmed the rumors. Then, on the night of October 24, Anna’s house was surrounded by a mob:

“For two hours we had the disagreeable noise of stones banging about, glass crashing, and the tumultuous voices of a large body of men, as they were a long time at the different houses in the neighborhood. At last they were victorious, and it was one general illumination throughout the town.”

Anna’s home and family escaped grave injury by relenting to the mob’s demand: placing lit candles in their windows to signal support for the victory at Yorktown. The Rawle family were being forced into showcasing patriotism. Other families, who refused the demands, were not so lucky; her neighbor, Mrs. Gibbs, “received a violent bruise in the breast and a blow in the face which made her nose bleed” while “John Drinker has lost half the goods out of his shop and been beat by [the mob]”.

Mission: Find the Girls

In the eight years of the American Revolution, girls bore witness to both its hopes and hypocrisies. Phillis used her pen to point out the continued enslavement of Blacks in a soon-to-be-free nation. Anna Greene Winslow used her domestic skills as a Daughter of Liberty to boycott British goods, while living as a British officer’s daughter. And Anna Rawle witnessed the victorious Revolutionaries force everyone in their new nation to adhere to their beliefs — even while proclaiming the rights that would soon be enshrined in the U.S. Constitution.

Their experiences are just a fraction of the many diaries and letters from girls and young women that can help us better document and explore the American Revolution. Unfortunately, many narratives focus on those who were adults at the start and end of the Revolution. We rarely ask what it was like to grow up during the Revolution. How did becoming an adult during the transition to a democratic nation affect the first generation of “Americans”? Did the young Daughters of Liberty engage in greater calls for equality — and if so, how did this affect suffrage, changes in fashion, women’s education, and other movements of the 19th century? Or do we see a pattern more akin to women’s roles after World War II?

To answer these questions, we must find the girls and their stories — and tell them.

If you know a primary source — diary, letters, etc. — of a girl in the American Revolution, please let me know in the comments. I am actively collecting digital copies in the hopes of creating a repository for future in-depth analysis. Thank you!